April 16, 2021

URCS Secretariat

Australian Government Department of Education, Skills and Employment

Executive Summary

To create a collective dialogue between the business and university sectors, the Group of Eight (Go8) and IP Group Australia convened two roundtable discussions on the topic ‘Research-led recovery: – how can Australia best leverage its university research excellence to drive increased sustainable growth?’. The aim of the discussions was to identify constructive measures to increase the economic and social dividend from Australian university research.

The roundtable covered many issues relevant to the development of a university research commercialisation scheme being consulted on by the Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE). This paper aims to present the thinking and outcomes of the discussion, distinguished by its cross-sector and collaborative nature, to further inform the government’s deliberations. We are aware that roundtable participants have made submissions to the DESE consultation paper in their own capacity. This is not aimed at replacing or superseding those submissions but highlighting areas where the views of participants from university, business and investment were aligned.

The roundtable discussions arrived at three high-level recommendations that participants agreed would be essential to making durable improvements in our research commercialisation performance. There was also discussion on specific areas to prioritise for action. These are set out below.

High-Level Recommendations

- A 10-year strategy for increasing translation of university research outcomes to economic benefit for sustainable growth.

- Clear accountability for delivery of the strategy to reside with a single area or Office of the Federal Government.

- Focus efforts in technologies, capabilities and markets where Australia can compete globally.

Specific Measures to Prioritise

- University sector policy to optimise and drive the translation relevance and readiness of research outputs.

- Introduce ‘impact’ as an assessed metric in funding decisions

- Programs to develop entrepreneurial talent within universities

- Provide more flexible career paths

- Staged translational funding programs to further develop the outputs of university research IP to a point of commercial engagement.

- Proof of concept funding to further develop promising research projects

- ‘Third-stream’ funding of business development capability within universities

- Increase ability of researchers to engage to help solve industry focused problems.

- Training and support programs for researchers

- Enable flexible movement between industry and academia

- Foster deeper engagement between academia, businesses and investors

- Intermediaries working between sectors

- Mentor program for SMEs

- Industry employment for HDR graduates

- Increase incentives for industry – university collaboration.

- Create a National Centre for University and Business to build relationships

- Increase support of private capital.

- Investment vehicles with risk-sharing between public and private capital

- Investment vehicles with risk-sharing between public and private capital

- Incentives to access risk-tolerant capital from high-net-worth individuals

Background

To create a collective dialogue between the business and university sectors, the Group of Eight (Go8) and IP Group Australia convened two roundtable discussions on the topic ‘Research-led recovery: – how can Australia best leverage its university research excellence to drive increased sustainable growth?’. The aim of the discussions was to identify constructive measures to increase the economic and social dividend from Australian university research.

The roundtables were held on 7 December 2020 and 22 February 2021, hosted by Professor Brian Schmidt, ANU Vice-Chancellor and Deputy Chair of the Go8.

Participants included senior representatives from across key stakeholder groups including university vice-chancellors, the Business Council of Australia, CEOs of research-intensive companies, the Chief Scientist, early-stage investors and major superannuation funds. A list of attendees is provided in Appendix A.

Discussion at both roundtables had strong engagement from participants, highlighting the importance of the issue to a broad range of stakeholders. Strong themes that emerged from the discussions are set out below.

It should be noted that while these roundtable discussions were convened by the Go8 and IP Group Australia, the intention was to arrive at a collective view owned by the group rather than to inform a position held by the conveners. It is expected that most, if not all participants, will make their own submissions to the URCS that will express their own views.

Vision

Our aspiration is to increase economic growth and social benefits from the investment in university research – through the technology, products and solutions it can generate – and for this to be sustainable and self-reinforcing. This goal takes on increased importance in the context of a recovery from COVID-19.

Context

Our future economic and social prosperity will depend upon research and innovation that will underpin rapid advances in the development and take-up of technology – in all of its forms. This technology will be central to creating a sustainable economy, to improving human wellbeing and staving off ecological collapse, and will underpin economic growth and the jobs of current and future generations. Technological leadership is also a core strategic consideration at a geopolitical level to build sovereign capability.

For Australia this presents a particular and urgent challenge. Our economy lacks diversity and scale, while we are also challenged by a lower-than-optimal proportion of leading technology companies with high growth potential[1]. This makes us vulnerable to global economic, environmental and geo-political shocks, as the COVID-19 pandemic and Chinese trade sanctions have highlighted. Without action to increase Australia’s sovereign capability in key technological and manufacturing sectors we are at risk of suffering lower productivity, slower economic growth, stagnating wages and higher unemployment.

Technological and other advances are underpinned by research and development, particularly in areas of national strategic importance. In Australia, more so than in other developed nations, R&D capability and spend is concentrated in our universities, which are therefore central to our ability to innovate[2]. Translating research outcomes requires expansion of successful university collaboration with business and industry partners to commercialise research through adoption of innovative technologies or creation of spinout- and start-up companies. We must significantly scale up the translation capabilities and outcomes of our university sector to bring it in line with, or surpass, global standards.

Australian university research is world-class, not least the vital basic research that underpins all outcomes from the pipeline, and that is a strength we can and must build on. We must also leverage more effectively our other strengths – the Australian Research Council and the National Health and Medical Research Council and their support of basic through to applied research, the Research and Tax Development Incentive, and more recently the Medical Research Future Fund.

There is an inherent tension in our current situation. There is an increasing recognition by universities of the need to translate the outputs of its research into the market, an increasing willingness of innovative business to engage, and a growing number of highly successful examples. At the same time, the pace of systemic improvement of our innovation system that is needed to support major scale up in commercialisation has been slow. There is no single cause, though factors include untapped opportunity, the failure to recognise and build on achievements, a fragmented policy environment, and a lack of consistency in prosecuting what does work.

More positively, we can capitalise on our experiences to build our future – if we take action now. There is a significant opportunity now to create an eco-system that will enable Australia to thrive in a world where technology is central to competitiveness, long-term productivity and jobs growth.

Framework

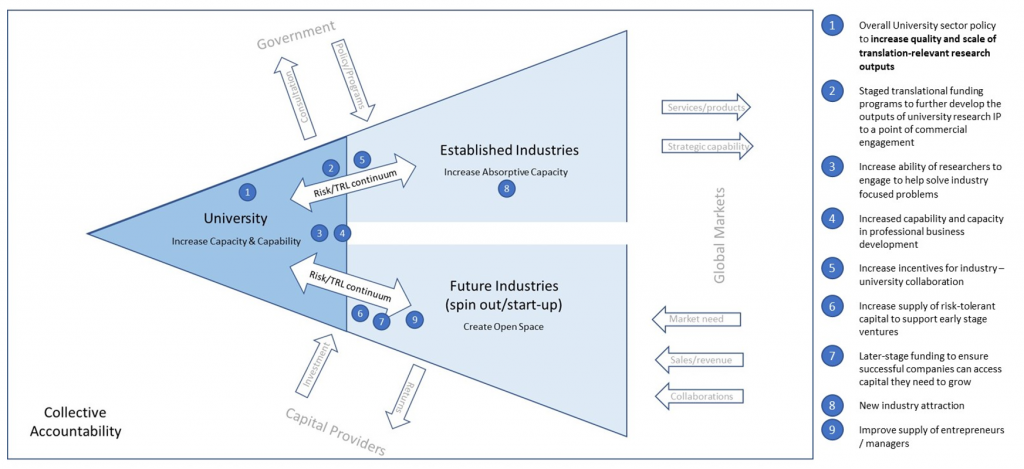

The following framework, considered by the roundtable, maps out and clarifies the relationships between the major players in the translation and commercialisation of university research.

Innovation is an unstructured contact sport. The impact that innovation delivers comes from this contact and the interactions between different participants in an ecosystem – between universities and business, between entrepreneurs and academics, between universities and policy makers.

The framework highlights the key interfaces in university research commercialisation – between universities and established industries, and between universities and future industries to take IP through the TRL/risk pipeline to successful implementation. It highlights the role of entrepreneurial capability to work with all stakeholders across the boundaries to enhance and create new companies. In order for innovation to take place at each of these interfaces, a given project or technology needs to be sufficiently advanced within the university environment to reach a point where industry or entrepreneurs / investors can engage, and similarly industry or entrepreneurs / investors need to have the skills and resources to be able to engage on the other side of the interface.

Against this framework, specific activities were defined and considered by the roundtable and are listed in appendix B.

The key conclusions from the discussion of the framework are the highly networked nature of the ecosystem, and the need for support measures to be holistic and responsive to a changing landscape. Collective accountability – between universities, industry and government – is essential for delivering outcomes that are to the benefit of all participants, and this flows through to the proposed recommendations.

Outcomes and Recommendations

High-Level

Three high-level recommendations emerged from the roundtable.

- A 10-year strategy for increasing translation of university research outcomes to economic benefit for sustainable growth. This plan needs to be developed jointly and owned by the highest levels of government, business and universities with a high degree of coordination across sub-groups of each. It would focus on the key prongs of human capital, investment capital, the players and how they interface with each other – namely research institutions (universities and publicly-funded research organisations) and industry.

A longer-term approach reflects that many measures required to increase translation take time to have effect and to yield results. Business planning cycles are also served by this extended timeframe. Policy consistency and coherence across multiple electoral cycles is needed to allow universities, researchers, industry and investors/entrepreneurs to respond, to shift the culture and to deliver outcomes.

Adopting a 10-year strategy is suggested to be a recommendation of the University Research Commercialisation Scheme. - Clear accountability for delivery of the strategy should reside with a single area or Office of the Federal Government. This office would coordinate across departments that engage with university research. A dedicated entity is required given the nature of university commercialisation as distinct from ‘startups’ in general. At present there are multiple departments and agencies (education, industry & innovation, health, defence) that are directly or indirectly involved with the translation and commercialisation of university research. As a result, policy measures can be disjointed and inefficient.

The Office should be supported by an advisory group comprising senior, knowledgeable representatives from the university, business, investment and entrepreneurship sectors. Informed by the advisory group, the Office would have a role to define and measure progress in a nuanced way, that acknowledges and learns from partial advances as well as complete success and helps refine our understanding of what is required. To create a world class system and ensure the best thinking and advice, appointing experts globally should be considered and not limited to Australian-based members. - Focus efforts in technologies, capabilities and markets where Australia can compete globally. This includes existing industries where Australia is a global leader, and new and emerging industries where Australian companies can become global leaders. Picking winners at the level of an individual firm is fraught. However, priority areas / missions should be identified where success can build on existing or future leadership.

The government’s existing priority industry sectors may provide a starting point. These will allow the winning combination of technologies, teams and companies to emerge that best leverage Australia’s advantage. Government may also define specific areas where our sovereign capability must be created or enhanced.

Implicit in this is that our current system of research and commercialisation funding does not provide the necessary focus and prioritisation. To drive meaningful change, either a new funding mechanism or substantive reform of existing mechanisms will be required. Importantly, decisions need to incorporate the views of industry, entrepreneurs and investors in addition to researchers and universities.

Specific Measures

The roundtable was presented with a list of specific measures (appendix B) that had been suggested to improve research commercialisation and asked to prioritise them. In addition, participants were asked to highlight priority industry or technology areas that could create a sector focus for the measures. The group was not by any means unanimous, but there was general agreement that the following areas should be prioritised.

- University sector policy to optimise and drive the translation relevance and readiness of research outputs. The current funding and incentive systems within the university sector are not sufficiently aligned with delivering translation or translatable outcomes. To maximise the impact of research spend on jobs and growth, these systems need to evolve to set the right incentives for institutions and researchers.

Any wholesale reform of granting bodies and processes will be challenging and will take time. Introducing ‘impact’ as an assessed metric in funding decisions was highlighted as one measure that has been successful in encouraging greater industry collaboration and commercialisation in the UK that could be piloted in Australia to inform future funding.

The need to focus efforts in areas where Australia can compete should be reflected in the priorities and assessment mechanisms for research funding and grants, potentially through the articulation of ‘missions’ or ‘challenges’ to define ambitious goals that are aligned with industry support.

Programs to develop entrepreneurial talent within universities, and to provide more flexible career paths allowing deeper engagement with industry are also important.

At the same time, it should be acknowledged that research commercialisation is not, and should not, be the sole focus of university research activities and that any reform should ensure that funding continues to be available for exploratory research which in itself is necessary to the entire research pipeline. - Staged translational funding programs to further develop the outputs of university research IP to a point of commercial engagement. A large proportion of promising projects or technologies within universities are not developed to a stage where industry or entrepreneurs/investors are able to engage with them. Existing grant schemes do not provide funding to progress them ‘the last mile’, and there is a shortage of capability and resources within many universities to assist their researchers in preparing for engagement with industry or investors.

Proof of concept funding is needed to further develop promising research to a point where industry or entrepreneurs are able to engage. This may include validating results, testing hypotheses, or constructing prototypes of a product or service. Such a program should ensure that external voices are represented in decision making and on investment committees, that it brings new perspectives into the university. Decision making should be local to empower local teams and ensure timeliness, but there should also be central information-sharing and co-ordination to ensure that the program can benefit from the national scale. An annual awards event should be considered to celebrate successful projects and provide role models.

Translation and commercialisation needs to be supported by business capability development within the university. So-called third-stream funding (i.e. direct government funding of knowledge or technology transfer capability within universities) has been successful in the UK in ensuring that the business input provided by university technology transfer offices have the resources to support activity and develop projects towards commercialisation. - Increase ability of researchers to engage to help solve industry focused problems. Researchers have historically been incentivized to value publication as an outcome and only lately have measures been introduced by universities and government to develop the skillsets they need to engage with industry or to translate their research. For them to do so requires overcoming a perception of risk to their career paths, the development of new skills, which can be intimidating, and run counter to their motivations for becoming academics.

In order to support researchers in developing these new skills, training and support programs as well as options to move interchangeably between industry and academia are necessary to give them the capability to engage and translate. Specific suggestions include the re-introduction of the CSIRO ON Program, industrial fellowships and a flagship ‘Entrepreneur Laureate’ program to introduce successful entrepreneurs into universities and provide high profile role models. - Foster deeper engagement between academia, businesses and investors. In addition to ensuring there is sufficient resourcing to support the progress of research ideas to viable investable opportunities, a ‘comfort zone’ needs to be created for industry to work with academia – whether through greater exposure to researchers via PhD placement programs, programs that support intermediaries working between sectors or mentors for SMEs, or efforts to encourage business to hire more staff with high level research degrees. While no specific suggestions were made at the roundtable for exemplars, there are several internationally and domestically that could be reviewed, including the Innovation Connections and CRP-P models, the APR Intern program, MTPConnect’s REDI program, CSIRO’s Industry PhD program, the UK industrial doctorate centres or France’s CIFRE.

- Increase incentives for industry – university collaboration. Creating stronger linkages between small, medium through to globally leading companies and universities (such as Boeing at the University of Queensland, Microsoft at the University of Sydney or Illumina at the University of Melbourne) is a critical driver of success. Beyond the initial benefits of research funding and innovation from the partnership itself, greater exposure and understanding of industry can shape research programs within universities and generate more spinout and startup companies.

At the same time, collaboration cannot be mandated. To achieve more collaboration an environment where linkages and collaboration are mutually attractive and incentivized should be fostered.

Practical suggestions for how to increase collaboration include the introduction of third-stream funding set out above which will increase the ability of universities to develop and manage industry partnerships with professional staff, creation of a body analogous to the National Centre for University and Business in the UK to support stronger relationships between senior leaders, and closely linking with state government policies on clustering and industry support.

The role of the superannuation industry in creating a sustainable step change in the contribution of university research to the broader economy is often underestimated. Through providing capital for the creation of new spinout and start-up companies by venture capital investors, the national wealth of Australians can be an increasing catalyst for economic growth in new industries. Conversely, improving commercialisation of university research will create new sovereign companies and industries that will provide greater growth, economic diversity and resilience investment opportunities for future retirement savings of Australians.

The superannuation industry

should be an important contributor to the discussion on university

commercialisation to ensure that the outputs are suitable for investment by the

industry. An obvious role is in providing capital to investors who are working

closely with universities to develop new spinout and start-up companies. Mechanisms

that enable the superannuation industry to share the risks associated with these

investments with government, such as the MRFF’s Biomedical Translation

Fund, can be helpful to catalyse greater availability of funding for new and

promising companies as they grow.

Beyond the superannuation industry, the roundtable discussed the role that individual investors can play in providing access to risk-tolerant capital for early-stage companies – even before they are suitable for venture capital investment. Improvements to the early-stage innovation company (ESIC) scheme for companies based on university intellectual property can provide one avenue to this. The recent introduction of the Knowledge Intensive Company branch of the UK Enterprise Investment Scheme provides one successful international example.

Conclusions

There is both an opportunity and a need for Australia to generate increased sustainable growth from its world-leading university sector. The roundtable discussions highlighted that capturing the opportunity will require concerted and sustained action across universities, business, government and the investment community. It will be necessary to draw all these stakeholders together to formulate a long term 10-year plan that provides a pathway to achieve the potential that is within the current system. Specific activities will need to vary to accommodate the changing economic and geo-political environment, but long term sustainable economic outcomes will require a long-term vision.

This submission highlights several actions that we believe can have significant impact and ensure that Australia can be a leader in the technological and practical advances of the 21st century and enjoy the benefits of improved productivity, growth and jobs.

Yours sincerely,

VICKI THOMSON

CHIEF EXECUTIVE, GROUP OF EIGHT

and

MICHAEL MOLINARI

MANAGING DIRECTOR, IP GROUP AUSTRALIA

Appendix A

Attendees – Roundtable 1

| Dr Thomas Barlow | Director | Barlow Advisory Pty Ltd |

| Mr Mark Burgess | Steering Group IP Group Australia | Investment Committee Chair, HESTA |

| Professor Michael Cardew-Hall | Emeritus Professor | Australian National University |

| Mr Jeff Connolly | Chairman and Chief Executive Officer | Siemens Australia |

| Dr Alan Finkel AO | Australia’s Chief Scientist | |

| Mr Tom Hockaday | Managing Director | Technology Transfer Innovation Ltd |

| Professor Peter Høj AC | Steering Group | IP Group Australia |

| Mr Dig Howitt | Chief Executive Officer and President | Cochlear |

| Professor Mark Kendall | Vice-Chancellor’s Entrepreneurial Professor | Australian National University |

| Ms Sue MacLeman | Chair | MTPConnect |

| Professor Duncan Maskell | Vice-Chancellor and Principal | University of Melbourne |

| Dr Michael Molinari | Managing Director | IP Group Australia |

| Dr Dean Moss | Chief Executive Officer, Uniquest | Chair, Go8 Innovation and Commercialisation Group |

| Professor Brian Schmidt AC | Deputy Chair, Group of Eight | Vice-Chancellor and President, Australian National University |

| Mr Sam Sicilia | Chief Investment Officer | Hostplus |

| Dr Jack Steele | Director, Science Impact and Policy | CSIRO |

| Mr David Thodey AO | Chair | CSIRO |

| Ms Vicki Thomson | Chief Executive | Group of Eight |

| Dr Jennifer Westacott AO | Chief Executive Officer | Business Council of Australia |

Attendees – Roundtable 2

| Ms Kiara Bechta-Metti | Director Commercialisation | University of Adelaide |

| Mr Mark Burgess | Steering Group IP Group Australia | Investment Committee Chair, HESTA |

| Professor Michael Cardew-Hall | Emeritus Professor | Australian National University |

| Dr Cathy Foley AO | Australia’s Chief Scientist | Office of Australia’s Chief Scientist |

| Mr Anthony Fortina | Deputy Director, Research Enterprise | University of Western Australia |

| Mr Hun Gan | Director, Business Development and Innovation | University of Melbourne |

| Dr Alastair Hick | Director, Monash Innovation | Monash University |

| Professor Peter Høj AC | Steering Group, IP Australia | Vice-Chancellor and President, University of Adelaide |

| Mr Dig Howitt | Chief Executive Officer and President | Cochlear |

| Ms Sue MacLeman | Chair | MTPConnect |

| Professor Duncan Maskell | Vice-Chancellor and Principal | University of Melbourne |

| Dr Michael Molinari | Managing Director | IP Group Australia |

| Dr Dean Moss | Chief Executive Officer, Uniquest | Chair, Go8 Innovation and Commercialisation Group |

| Mr Mike Pope | Senior Policy Adviser | Business Council of Australia |

| Professor Brian Schmidt AC | Deputy Chair, Group of Eight | Vice-Chancellor and President, Australian National University |

| Mr Sam Sicilia | Chief Investment Officer | Hostplus |

| Dr Elaine Stead | Interim Director, Technology Transfer Office | Australian National University |

| Dr Jack Steele | Director, Science Impact and Policy | CSIRO |

| Mr David Thodey AO | Chair | CSIRO |

| Ms Vicki Thomson | Chief Executive | Group of Eight |

APPENDIX B

Long-list of potential measures presented in discussion paper for Roundtable 2

(numbers correspond to the framework diagram)

- Overall

University sector policy to increase quality and scale of translation-relevant

research outputs

- Create entrepreneurial talent development programs to drive academic careers focused on engagement rather than publication

- Introduce a scheme to recognise, promote and celebrate researchers that engage with industry and/or spinouts

- Create and extend senior-level relationship forum between universities and business based on the UK’s National Centre for Universities & Business

- Build on the Engagement and Innovation Assessment and link impact measures such as a university’s commercialisation performance (measured effectively) to meaningful funding outcomes (following the UK example)

- Reform funding councils to provide balance between medical and physical science and engineering. Establish Physical Science and Engineering council to sit alongside NHMRC

- Create a ‘Missions Fund’ to support translationally focussed research in targeted areas

- Introduce translational research fund (ex-medical) in line with the MRFF with various sub-programs

- Create

staged translational funding programs to further develop the outputs of

university research IP to a point of commercial engagement

- Funding for proof-of-concept funds within universities with clear deliverable measures and implementation guidelines (must involve external parties)

- Re-focus and expand ARC Linkage programs

- Expand CRC-P program

- Focused sector translational funding aligned to national missions coordinated with state programs such as the NSW Medical Device Fund

- Increase ability of researchers to engage to

help solve industry focused problems

- Researcher training programs

- Doctoral Training Centres

- Translational PhD scholarships

- PhD and Post Doc Internships

- Translational (Post Doc) Fellowship

- Industrial Fellowships (from university to business and vis versa)

- Entrepreneurial Laureate

- Researcher training programs

- Increased capability and capacity in

professional business development to reduce friction at the researcher-business

culture gap

- Third-stream funding for professional business development staff within universities

- University-Business Development Apprenticeships

- Develop standard-form knowledge transfer documentation, where appropriate

- Increase incentives for industry – university

collaboration

- R&D Tax Incentive collaboration premium for business

- Increase HERDC weighting for Category 2/3 funding

- Business R&D vouchers for engagement with university research

- Increase supply of risk-tolerant capital to

support early stage ventures (pre-seed, seed)

- Tax incentives to encourage investment from high net worth individuals into university spinout companies (for example recent introduction of the ‘knowledge intensive company’ Enterprise Investment Scheme rules in the UK)

- Early-stage seed funds – provide management fee subsidies to investment managers that focus on university IP seed funding

- Later-stage funding to ensure successful

companies can access capital they need to grow

- Create patient capital (deep tech) funds matched public to private funding. Structure funds to encourage and incentivise the participation of superannuation funds, potentially through preferential economics above a cost-of-capital return to public funds

- Introduce support for ‘knowledge intensive companies’ into the benchmarking exercise for superannuation funds (current proposal could have a negative impact on ability of superannuation to support the sector)

- New industry attraction

- [Is there a scheme to support bringing globally significant companies onto campus to increase absorptive capacity, such as the UoM relationship with Illumina, USyd with Microsoft and UQ with Boeing?]

- Improve supply of entrepreneurs / managers

- Entrepreneurs Relief tax treatment

- Programs to support entrepreneur / senior talent attraction.

- Support entrepreneurial training programs for academic staff (researchers, post-docs, PhDs)

- Visa policy to enable/support above

[1] The Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources 2020 Australian Innovation Monitor notes that since 2007–08, Australia’s proportion of high growth firms HGFs as measured by employment has steadily fallen from 7.2 per cent to 5.2 per cent in 2016–17

[2] Australia has a relatively high proportion of researchers working in universities at just over 60% of total researchers versus for example France (26%), Germany (26%), Japan (20%) or the UK (54%). In addition, as a percentage of national GDP Australian R&D spending in Higher Education (0.62%) is well above the OECD average (0.41%) and other major economies such as the US (0.36%), the UK (0.41%), France (0.45%), Germany (0.55%), Japan (0.38%) and Israel (o.43%). This is despite Australia’s overall investment in R&D as a percentage of GDP at 1.79 being well below the OECD average of 2.47. Data is based on latest ABS surveys on Research and Experimental Development for Higher Education, Business and GOVERD and OECD Main Science and Technology Indicators.